David Stevens is Executive Strategy Director at global brand consultancy, Wolff Olins. He specialises in leading big, creative transformation projects with brands who need a new voice, a new identity and a new story. Recently, he’s worked with the BBC, abrdn, McKinsey, Google and TikTok. He has also written extensively on the future of brands and culture for Creative Review, Campaign, The Drum and WARC and pens a monthly column for Little Black Book. He’s also written about writing, including an opinion piece called ‘Write to excite’.

A company has a lot on its plate and might not prioritize creating a brand voice. What would you tell a company without a clearly defined brand voice? Why do you think having a brand voice is important?

I think that a lot of people secretly hate reading and writing. And they certainly hate writing anything for public consumption that will reveal their sub-par grammar.

Client decks, social posts, advertising headlines, legal copy—writing these things can induce mild panic attacks in the best of us. I think that’s because people (consciously or not) associate formal writing with school and doing essays, plus it’s similar to public speaking where you’re putting something out there to be torn down.

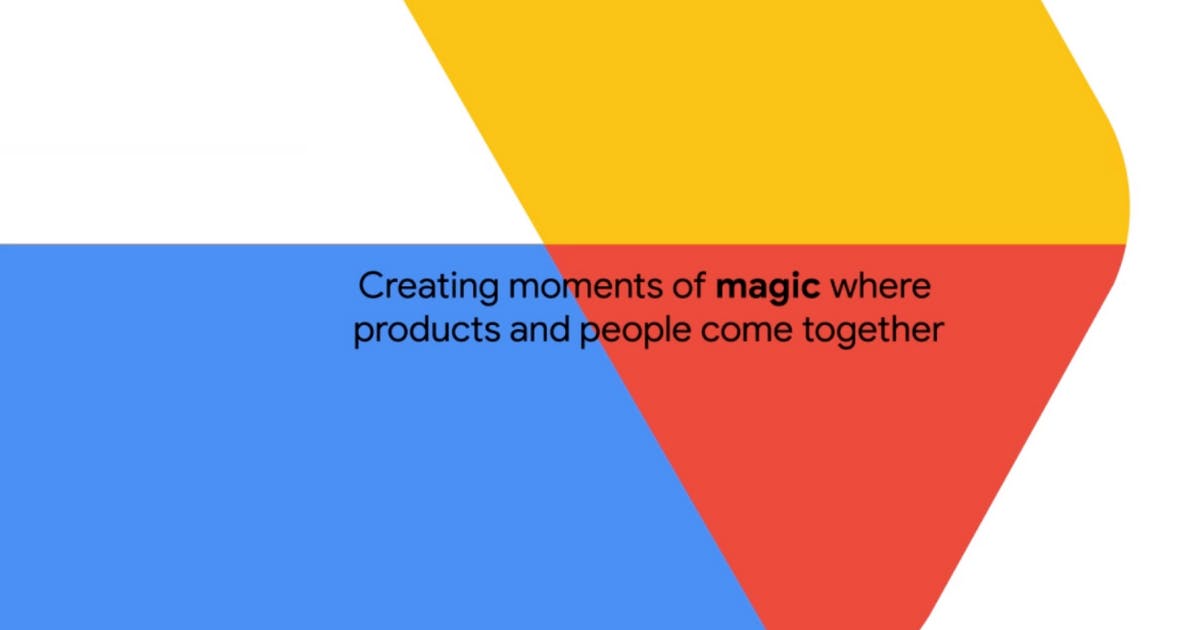

Wolff Olins for Google

It’s not quite like that with visuals and graphics—they’re more akin to art. Visuals are ‘read’ in a more automatic, less analytical way. So when you think about a brand in your mind’s eye, you tend to think of how it looks, tastes, feels… not how it reads or speaks.

People get excited about a rebrand when it’s visual (‘Yay, we’re gonna look cool!’) but they find it hard to enthuse about voice and words (‘Yay, we’re gonna learn how to…write?’).

But then when you think hard about what brands you actually love-- whether that’s Nike, Oatly, Paddy Power, or Google-- you realise that you love them because they speak to you. They have an attitude, a swagger, a sense of humour, a point of view you can identify with… and all this is delivered through a voice.

Wolff Olins for McKinsey & Company

Until you hear a brand talk to you, provoke you even, it can all be just a bit… nice. A bit… quietly hanging around like cultural wallpaper. So instead of thinking about a voice as that boring bit about words, think about it as the bit that’s all about attitude.

What’s the essential first step any company should think about when developing a brand voice?

It’s really good to start by asking: Where’s our voice coming from? Is it speaking down to you from on high? Is it with you in the trenches? Is it a voice you’d hear at the pub? Or is it almost straight-up the voice of a founder?

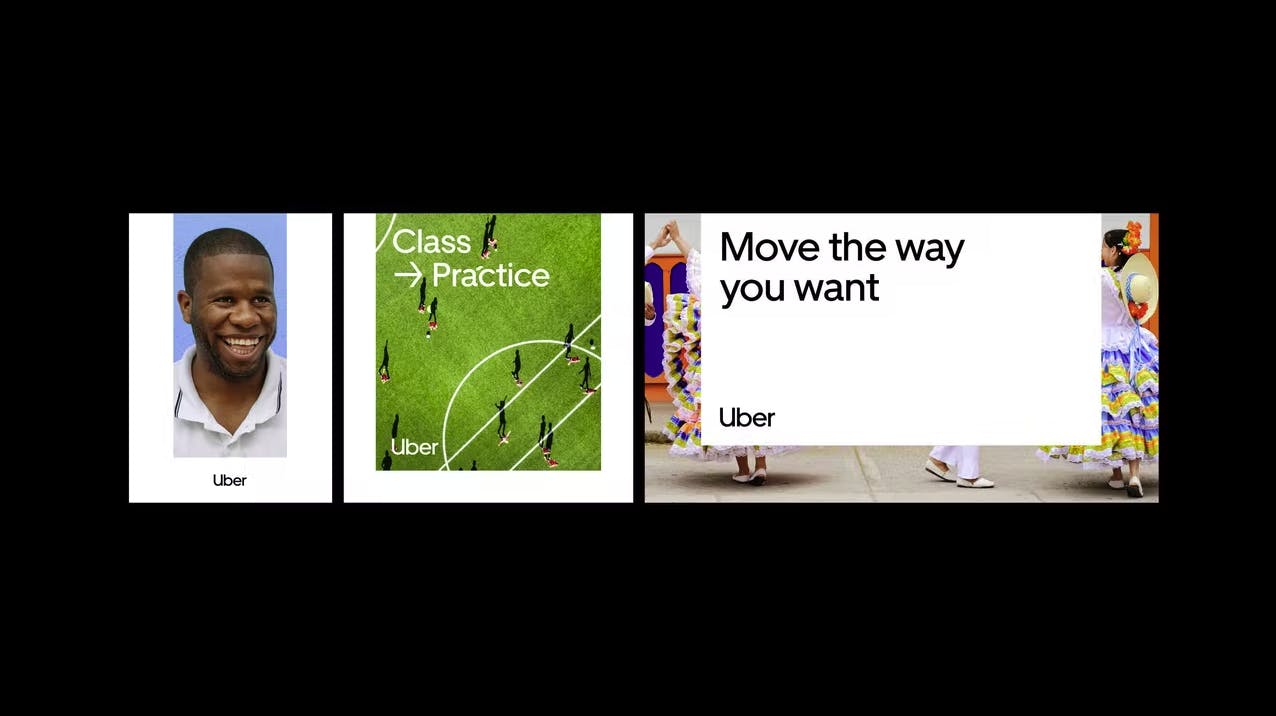

Wolff Olins for Uber

Until you know where your voice is really coming from, you risk of debating generic adjectives like ‘witty’ and ‘bold’. Nike’s voice comes from the relationship between coach and athlete. Paddy Power’s comes from office and pub banter. Ben & Jerry’s voice comes fresh from a Vermont ice cream parlour.

Why do you think brand voice should be emotional? Or, alternatively, what would you say is the cost to brands if they’re not writing with feeling or writing to excite?

If you want your brand to be remembered, chosen, loved, recommended… you’ve got to get people talking. If you’re the kind of person who believes that’s best achieved by offering them dry information, endless proof points, instruction manuals, legal clarity… then fine, good luck to you.

Wolff Olins for Grubhub

I believe people want to feel a connection, some passion, some confidence, some energy. They want to feel that you’ve got this and you get this - whatever ‘this’ is.

What sort of research do you think brands need to do before they start creating a brand voice?

Look for the category cliches. Loads of car brands play on the idea of having ‘drive’ and being ‘driven’. Loads of food and drink brands talk about something being a ‘mark of good taste’. Countless brands spend the Christmas period telling you they’ve got everything ‘all wrapped up.’

Brands think they’re being clever and witty by looking for double meanings. But they’re falling into the same old trap: wordplay. Great writing is not wordplay.

If it was, you could become a great writer by buying a bunch of fridge magnets. So, look out for the cliches, then work out how to avoid them or subvert them.

Do you have any tips or guidelines on how brands can approach picking an emotion or vantage point that they should use?

The obvious answer (which I think is still a good answer) is to write with the emotion in mind that you want people to feel. This is good because you aim for your writing to feel a certain way, rather than just repeating keywords (which will bore people very quickly).

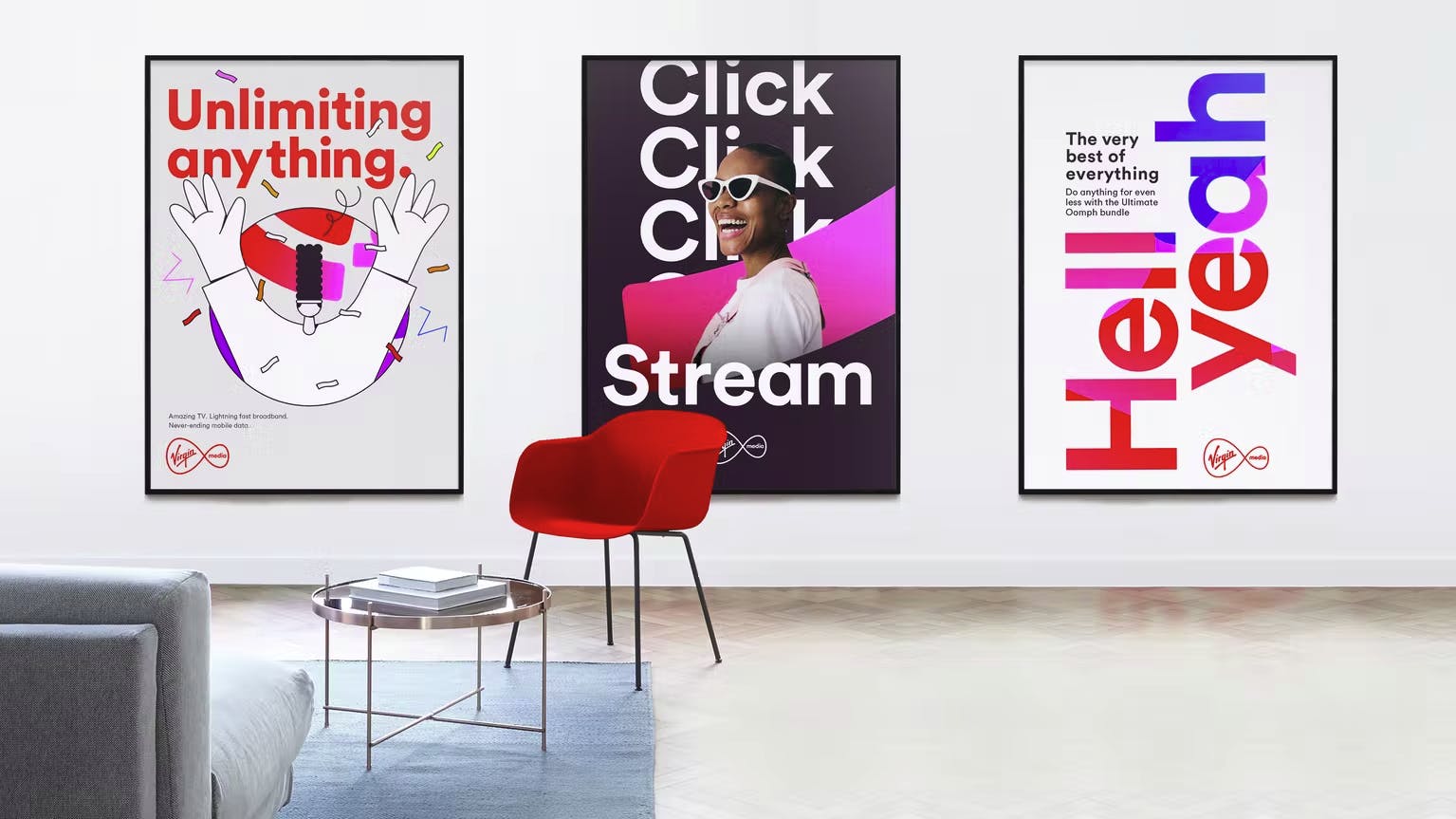

Wolff Olins for Virgin Media

A different approach is to think about your enemy. To rail against it, to use your nemesis as your motivation and your target. This can generate a lot of energy and is a great way to identify with people. Basically, have a rant.

You mention that brands shouldn’t “over-egg the pudding,” and there have been times when brands have attempted to write to excite but it doesn’t go well for them. Do you have any advice so they can avoid that?

Nike doesn’t say ‘Just Do It’ on every product, in every ad, on every shoebox. Tesco doesn’t tell you that ‘Every Little Helps’ on every app screen or every receipt. Instead, both of these brands look for opportunities to inject personality and passion into the right places.

Wolff Olins for Tesco

So rather than just plonking their tagline on a recycled plastic bag, Tesco says ‘I’m back’. And rather than just telling people to ‘do it’ on Air Max Day they say ‘KISS MY AIRS’. It’s witty, original, it has attitude, it’s from the same place, and it’s not just repetition.

Do you have any tips for brands for execution or establishing their brand’s voice with their audience and sustaining that over a long period of time?

I think all brands need to reflect popular culture and vocabulary to some extent. Sure, TikTok and ASOS need to feel more current than the British Library, but all brands need to accept that language evolves and how people speak is always in flux.

It’s important not to just fiddle around with adjectives, and instead be conscious of your cultural references.

For example, if you’re writing for Tesco and you know you need to channel a kind of dad-joke, light entertainment energy, are you still looking at Bruce Forsyth for inspiration, or are you listening to how Ant and Dec speak on Saturday Night Takeaway?

Wolff Olins for AXA

If you’re writing a Nike football campaign, are you writing like a bald guy in a blazer on Match of the Day, or are you using the vocabulary of Netflix’s Top Boy?

If you want to write to excite, you’ve got to beware cliches and fading cultural references and try to stay alive to all voices, whether they’re from the street or the stars of primetime.